A special place, and a crucial time

- August 24, 2014

- / Rick Harper

- / report-pensacola-metro-2014,economy

Dr. Rick Harper serves as senior research fellow with the Studer Community Institute, a

Pensacola-based organization that seeks citizen-powered solutions to challenges the community faces.

In early 2001, then-Pensacola News Journal Executive Editor Randy Hammer sent UWF’s Haas Center for Business Research and Economic Development an invitation:

“Pensacola has a long and rich history, but things are changing,” he wrote. “Growth and wealth have shifted to the east, and those communities don’t have some of the problems that are the legacy of our older city. Help us paint an economic picture of our community. It should be data-driven and tell what’s good and what’s not so good. For community leaders to work together to make things better, they have to know where to begin.”

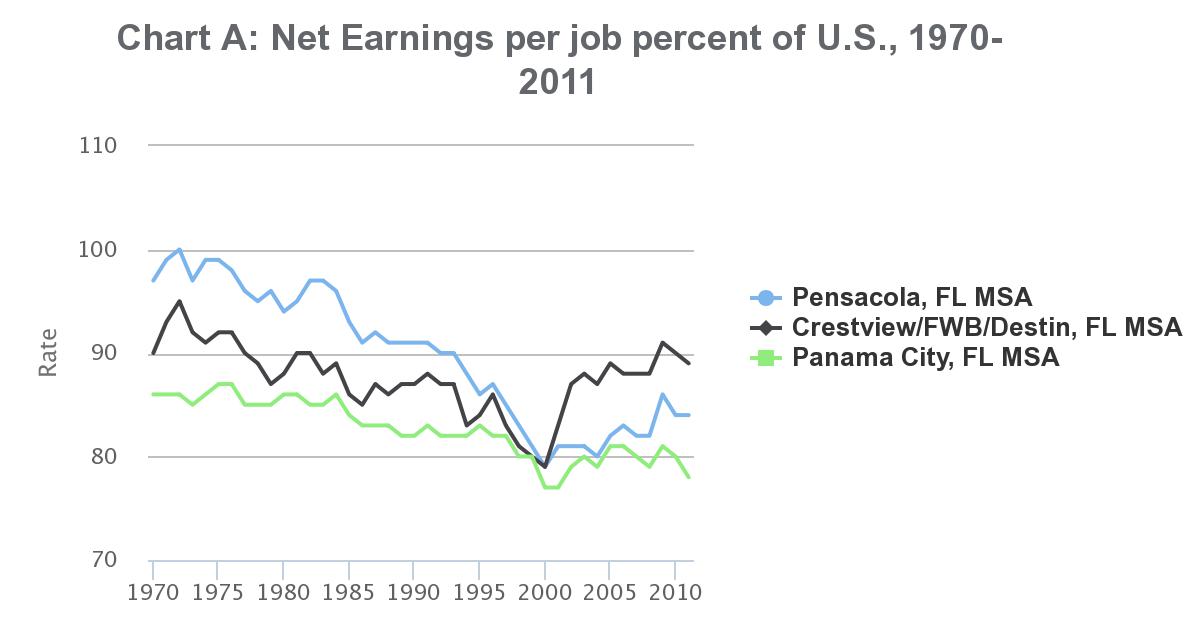

The Haas Center worked with the PNJ to produce a 64-page report on the region’s economy. Put your hand over the 2000 to 2011 period in Chart A to see how the data looked as we put together the 2001 project. What was striking then was the decline in labor income for West Florida relative to the national average.

What was even more striking was Pensacola’s decline relative to Fort Walton Beach and Panama City in the last three decades of the 20th century. Happily, several things have changed since 2001. The good news has been a rebound in earnings per job that lasted an entire decade. But it wasn’t enough to catch us up to where we were before the 1990s.

What caused job losses?

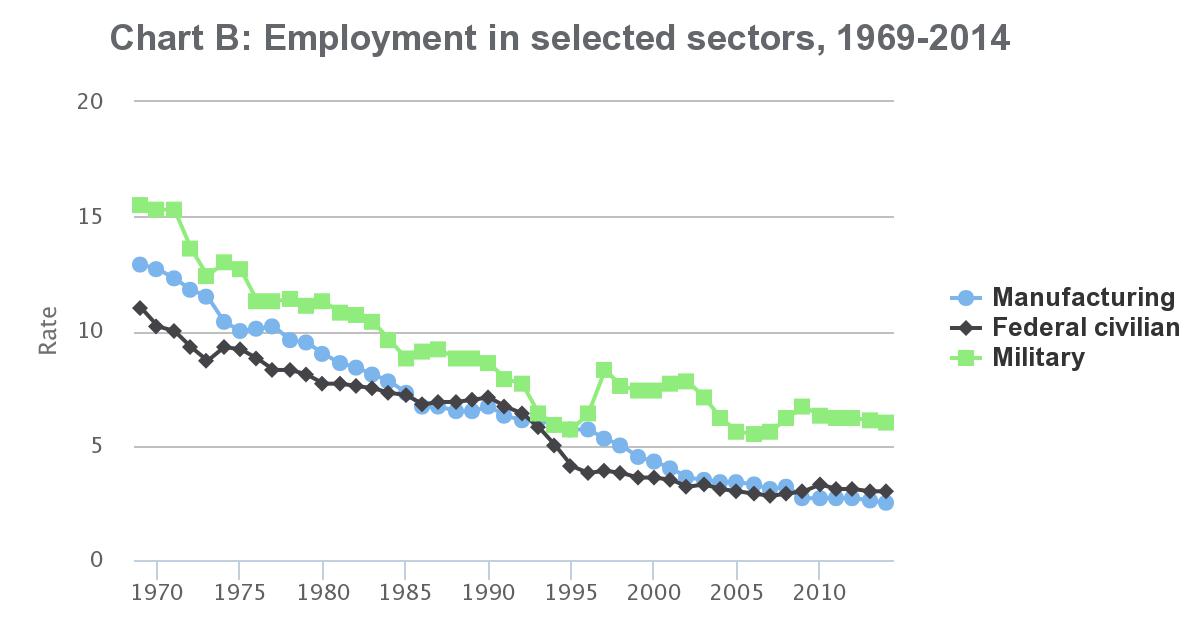

Much of Pensacola’s wage decline relative to the national average over those 30 years was driven by a sharp fall in manufacturing jobs and by shrinking federal employment. While we still produce a substantial volume of paper and nylon products at International Paper and Ascend Performance Materials, we do it using far fewer people — thousands of high-wage manufacturing jobs are gone for good. The federal civilian jobs lost at the Pensacola Naval Aviation Depot are also gone for good, while overall employment to support other military missions has also declined.

To some extent, these changes were unavoidable and simply mirror the national experience, although our own manufacturing job loss has been more extreme.

- The number of jobs in manufacturing fell by 56 percent in Pensacola over the 1969-2014 period, while it fell by 36 percent nationwide.

- The number of jobs in federal civilian and military employment fell by 23 percent in Pensacola over that period, while it fell by 20 percent nationally.

Because jobs in other sectors of the economy generally have grown over time, manufacturing and federal job performance look even weaker when measured as a share of the overall economy. Back in 1969, manufacturing and federal employment (military plus civilian) made up 39.4 percent of total employment and paid 49.4 percent of total wages in our two-county area.

By 2014, those shares had declined to 11.5 percent of employment and 25.5 percent of total wages.

Even though we have fewer military jobs than before, those jobs pay well. In fact, much of the rebound in earnings per job following 2001 has been due to the Bush ramp-up in defense spending.

Nationally, enlisted pay rose 40 percent and officer pay 20 percent over the decade, while private sector wages were stagnant or falling. A statistical look across the 380 metro areas in the United States shows a strong correlation between income growth and the share of military jobs in the local economy. While this is encouraging for a community like Pensacola, it isn’t likely to persist in an age of sequestration and base realignment and closure.

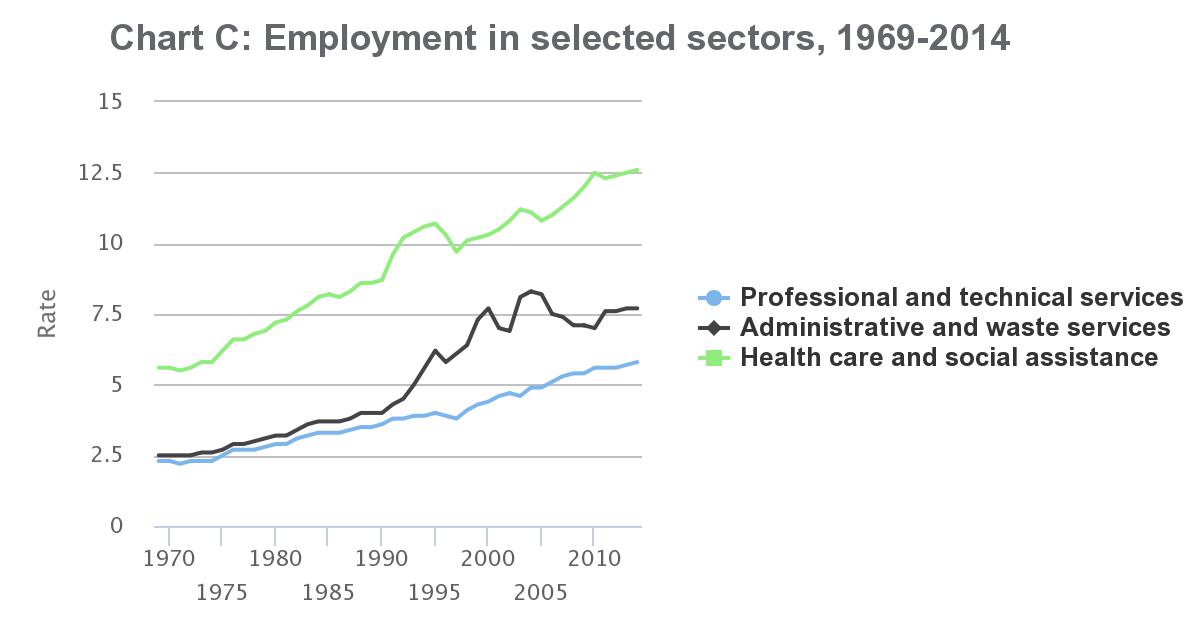

Service sectors have grown

In the meantime, jobs in the service sectors have grown. The healthcare service sector has doubled its share of the economy. Other services have grown as well, particularly call centers. The accommodation and food services sectors, while large, have not grown as rapidly as health care. Our tourism sector has always been large, and it has held its own in importance in the economy.

Much of the focus in 2001 was in comparing Pensacola to our faster-growing neighbors in Fort Walton Beach and Panama City. The conclusions we reached then still hold. Fort Walton Beach and Panama City closed the wage gap with Pensacola between 1970 and 2000; since then, Fort Walton’s wage growth has outpaced both Pensacola and Panama City. This is mostly due to wage growth in the military and in defense contracting. There is no other county in Florida where military employment has a larger share of the economy than in Okaloosa.

Income from wealth and income from government transfer payments

There is more to personal income than wages, alone.

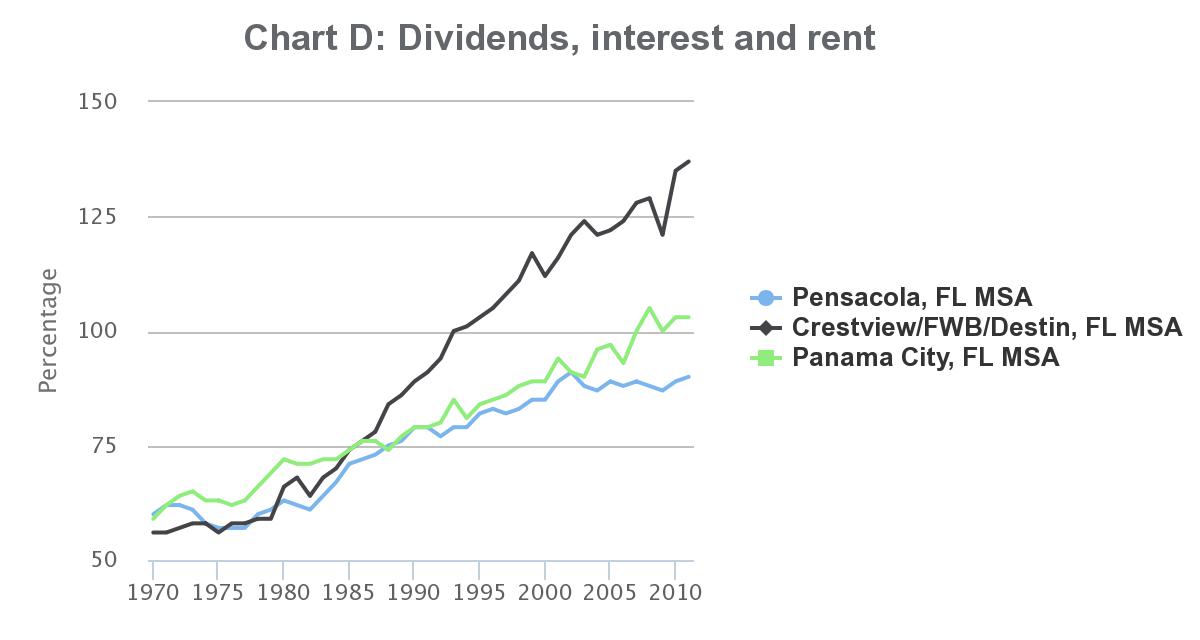

Personal income is measured by wages and other income to labor, income from accumulated wealth (from dividends, interest and rents), and transfer payments from the government, which increasingly over time in the U.S. go to older Americans (as opposed to poorer Americans). Charts D, E and F present these measures.

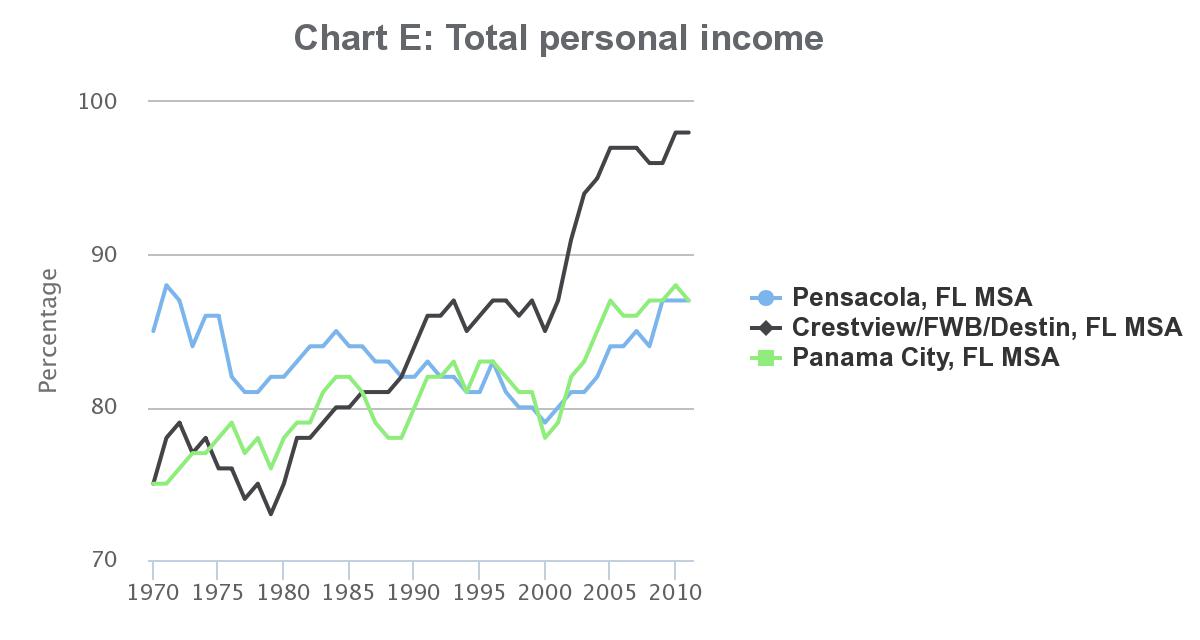

Once other sources of income beyond wages are added to the picture, we get a picture of total personal income. All of the coastal metros look better under this measure than under the labor income measure, but again, Fort Walton comes out on top. In order to explain these differences between metro areas in our Northwest Florida region, we need to look at the components that make up personal income.

Much of the explanation for the rise in total personal income, even as labor income was falling, is the 2013 inclusion of Walton County in what the U.S. Census calls the Crestview-Fort Walton Beach-Destin metropolitan statistical area. Inclusion in a metro area depends on commuting patterns, and the links between Okaloosa and Walton counties have become stronger over time. Okaloosa has been home to the most concentrated federal military, civilian and defense contracting employment in Florida. Walton County, which has always had a relatively small population and a robust tourism presence, has seen a large increase in the number of retirees who call South Walton home.

An influx of wealthy retirees appears to fuel a large increase in earnings flowing from accumulated wealth. While all three coastal metros have improved relative to the nation, growth has been exceptional for Fort Walton, whose trend diverged from Pensacola and Panama City in the early ’80s. Over the 1970-2011 period, per capita income from wealth grew from $1,409 per resident per year to $8,818 (in 2009 dollars) in Fort Walton, while it grew from $1,506 to $5,810 in Pensacola.

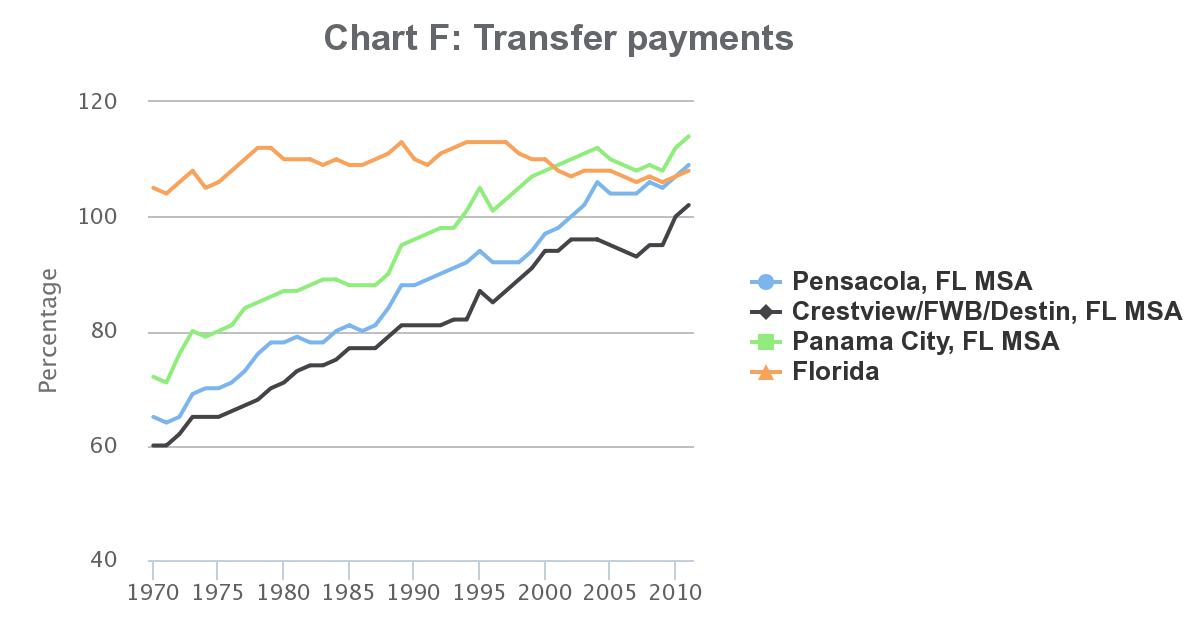

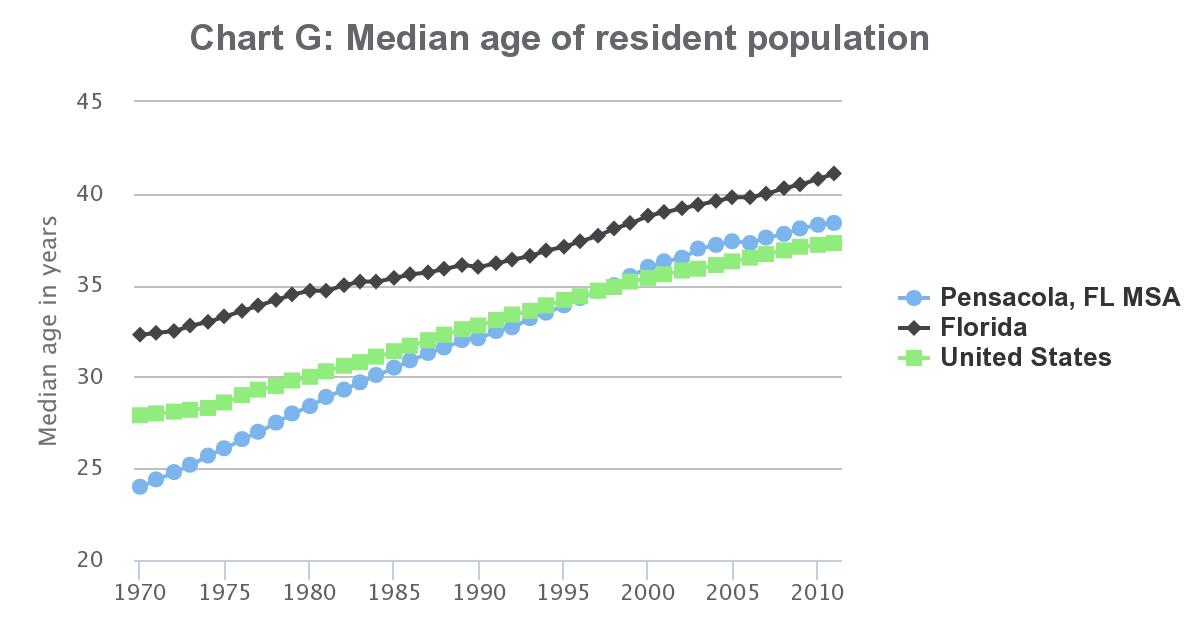

The growing attractiveness of Pensacola as a retirement location, combined with an outbound migration of younger people seeking economic opportunity, has led to the median-age Chart G. That chart sheds some light on why transfer payments in our region have increased, as shown in Chart F.

A large and perhaps not widely recognized phenomenon is that our Northwest Florida demographics are starting to look more like Florida in terms of age. This is important because transfer payments in the U.S. are targeted largely at senior citizens, with the biggest programs being Social Security and Medicare. These are called transfer payments because they are not a payment for current effort. They are instead a means-conditioned payment for work done earlier in one’s life.

Chart F shows that transfer payments to Floridians have been somewhat unchanged relative to the national average. Florida has always attracted a large number of retirees, but Northwest Florida is now increasingly a destination for older residents, and thus their transfer payments.

The bottom line

What is the takeaway from the information presented here? The most basic story is actually a good one. Our per capita personal income, which fell relative to the nation for the last three decades of the 1900s, recovered dramatically in the 2000s. It now stands at 87 percent of the national average, which is as high as it has been in any period during the last two generations.

However, that income now comes from different sources than it once did. Our median age in 1970 was 24, now it is 38 — we’re 14 years older, while over the same period the median age for Florida and the nation increased by 9 years. Age has its privileges, and one of them is retirement pay and medical benefits funded by the U.S. taxpayer. Moreover, older people are on average wealthier than younger ones, and the dividends, interest and rent that flow to owners of wealth now flow more to Pensacolians than they did 45 years ago. We’ve shifted out of manufacturing and government jobs and into services jobs and retirement income.

What does the future hold?

The reality of the 21st century workplace is that cost-lowering innovation in technology (e.g., automation) and globalization (e.g., containerization) provide relatively few high-wage work options for people doing tasks that can be automated or done offshore. This change has been a disaster for people who decades ago would have earned a reasonable wage on the assembly line and in many other jobs.

But on the upside, higher incomes now flow to those who design and run the automated processes or who can sell their skills across the globe. Just look at NBA teams who have started to play regular season games overseas. And English soccer star David Beckham that wants to build a stadium in Miami. Both high and low-end retailers have expansion plans, while middle-class retailers like JC Penney’s and Sears fade away.

Our sense that the middle class faces challenges and that intergenerational poverty is hard to eradicate match our national experience. Recent academic work finds that the United States has not seen improved intergenerational class mobility relative to peer nations, despite decades of spending associated with the War on Poverty. The same factors that spur luxury sales also increase income inquality and limit the growth of a middle-class market that might otherwise buy expensive new products and technologies.

The residents of a community use a variety of assets, including labor, capital assets, good ideas and hard work to create economic activity and wealth. Some, such as oil and gas reserves, are specific to a particular geographic location – the oil and gas fields of North

Dakota have transformed economic opportunity for that area. The reality of the 21st century is that many productive assets can be located anywhere and the skills and abilities of our residents determine how well we perform relative to our neighbors.

The best chance for our local middle class to perform well in the modern economy is to prepare our residents for the high-wage jobs of the future and to create economic opportunity across the board. This calls for:

- Ensuring that as many children as possible show up for their first year of school ready to learn.

- Maintaining high achievement across the K-12 system so that more of our youngsters finish high school either ready for university, for college, or for work.

- Making ongoing workforce training more readily available, since workers switch jobs more often.

- Promoting population growth for our community. Economic opportunity happens when there are new customers and workers, not when there is stagnation.

- Capitalizing on our unique access to areas that are opening to subsea drilling and exploration by promoting services aimed at that industry.

- Promoting visitation and relocation to our historic and beautiful community.

- Supporting growth of quality educational programs at our colleges and university.

If we can provide a community with safe streets, good schools, and the economic opportunity that comes with a growing population, then many of the challenges we face will take care of themselves.

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs