Helping Washerwoman's Creek find daylight

- October 23, 2014

- / Carl Wernicke

- / community-dashboard

Digging up a piece of Pensacola’s past could turn out to be a way of creating a drier future for downtown Pensacola.

With development adding more paved surfaces like parking lots, and climate change threatening to stimulate stronger, more intense rainstorms, concern is growing about repeated flooding, especially in downtown Pensacola. A damaging flood in April prompted new efforts to find solutions.

Much of the focus is on Pensacola’s old drainage system, which has been expanded, patched and repurposed over many decades. Both the City of Pensacola and Escambia County are conducting engineering studies and adding up the cost in an attempt to find solutions.

As part of the solution, city resident Eric Mead, an attorney, is proposing to go back to the future by “daylighting” a creek that disappeared long ago — but which still flows underground through the west side of downtown.

To trace the path of the creek, Mead recently co-led a tour sponsored by the Northern Gulf Coast Chapter of the U.S. Green Building Council. Tour leaders included Christian Wagley, an urban design consultant who owns Sustainable Town Concepts; Dr. Elizabeth Benchley, director of the Division of Anthropology and Archaeology at the University of West Florida and UWF’s Archaeology Institute; and Brad Hinote, a city engineer.

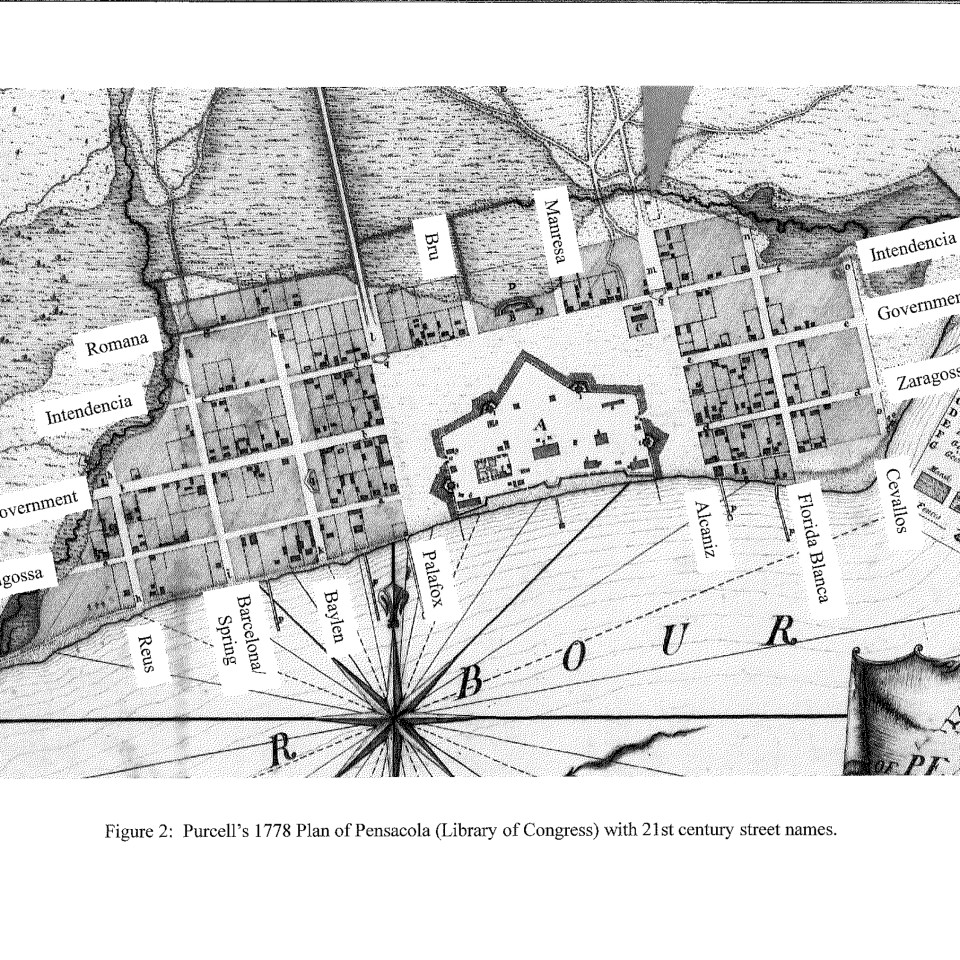

We followed the course of San Gabriel Creek, also known as Washerwoman’s Creek, which once provided both drinking water and wash water for early downtown residents. The spring-fed stream drains portions of North Hill and downtown, and the tour began at the Garden Street-Spring street intersection, where the creek flowed out of what old maps show as a large wetland.

The springs and creek are still there, flowing underground down Spring Street, then veering west past City Hall and the complex of state office buildings and on through the old site of the Main Street Sewage Treatment Plant. That plant, badly damaged by storm surge from Hurricane Ivan in 2004, stood on fill that covers the mouth of the creek, which resurfaces south of Main Street by the Nick’s Boathouse sign. (The plant has been relocated to higher ground.)

[caption id="attachment_7261" align="alignright" width="300"] The outfall of what was Washerwoman's Creek near the sign for Nick's Boathouse in downtown Pensacola.[/caption]

In downtown Pensacola, we were told, the wetlands and creeks the Spanish settlers found – and almost immediately began filling – are still there. We can’t see them until heavy rains come. Then the ground quickly saturates and the floodwaters rise.

Wagley said the practice of trying to bury wetlands and creeks isn’t unique to Pensacola; it has been done almost everywhere. In Pensacola the Spanish, who established a permanent settlement in Pensacola in 1698, began the filling; the British continued it in creating the garden plots that became Garden Street, and in the 1880s and ‘90s the city finished off the remaining downtown wetlands by dumping municipal garbage as well as debris from a big downtown fire.

Another buried creek, which might be a future tour, flows underground to the east, past St. Michael’s Cemetery to an ancient wetland we now call Aragon.

Mead argues that “daylighting” San Gabriel creek — removing the asphalt, dirt and debris covering it — to restore the old creek basin would help control flooding, reduce flood insurance premiums, improve water quality and create an attractive green corridor that could be lined with walking paths.

And, counter-intuitively, it should also facilitate development on the west side of downtown.

There is a surprising amount of undeveloped, and underdeveloped, land along the creek basin, which is still discernible despite the apparent flatness of downtown. Mead said the high water table and saturated, mucky soil make it expensive to build stable foundations. One moderate-sized building required digging out and replacing 15 feet of muck with red clay. I later talked to a builder who confirmed the difficulty of working in that part of town.

Daylighting has been done successfully elsewhere, sometimes paid for with bonds repaid out of new tax revenue produced by property tax growth from new development.

It would likely cost millions of dollars to uncover the estimated 3,000 linear feet of San Gabriel Creek that could feasibly be daylighted. Mead holds out hope that it could be part of a comprehensive downtown drainage solution, and suggests it could even be cost-competitive with trying to replace old drainage pipes with bigger ones.

Which is ironic when you consider that had we simply lived with the creek as nature designed it, we would have had all these benefits for free.

The outfall of what was Washerwoman's Creek near the sign for Nick's Boathouse in downtown Pensacola.[/caption]

In downtown Pensacola, we were told, the wetlands and creeks the Spanish settlers found – and almost immediately began filling – are still there. We can’t see them until heavy rains come. Then the ground quickly saturates and the floodwaters rise.

Wagley said the practice of trying to bury wetlands and creeks isn’t unique to Pensacola; it has been done almost everywhere. In Pensacola the Spanish, who established a permanent settlement in Pensacola in 1698, began the filling; the British continued it in creating the garden plots that became Garden Street, and in the 1880s and ‘90s the city finished off the remaining downtown wetlands by dumping municipal garbage as well as debris from a big downtown fire.

Another buried creek, which might be a future tour, flows underground to the east, past St. Michael’s Cemetery to an ancient wetland we now call Aragon.

Mead argues that “daylighting” San Gabriel creek — removing the asphalt, dirt and debris covering it — to restore the old creek basin would help control flooding, reduce flood insurance premiums, improve water quality and create an attractive green corridor that could be lined with walking paths.

And, counter-intuitively, it should also facilitate development on the west side of downtown.

There is a surprising amount of undeveloped, and underdeveloped, land along the creek basin, which is still discernible despite the apparent flatness of downtown. Mead said the high water table and saturated, mucky soil make it expensive to build stable foundations. One moderate-sized building required digging out and replacing 15 feet of muck with red clay. I later talked to a builder who confirmed the difficulty of working in that part of town.

Daylighting has been done successfully elsewhere, sometimes paid for with bonds repaid out of new tax revenue produced by property tax growth from new development.

It would likely cost millions of dollars to uncover the estimated 3,000 linear feet of San Gabriel Creek that could feasibly be daylighted. Mead holds out hope that it could be part of a comprehensive downtown drainage solution, and suggests it could even be cost-competitive with trying to replace old drainage pipes with bigger ones.

Which is ironic when you consider that had we simply lived with the creek as nature designed it, we would have had all these benefits for free.

The outfall of what was Washerwoman's Creek near the sign for Nick's Boathouse in downtown Pensacola.[/caption]

In downtown Pensacola, we were told, the wetlands and creeks the Spanish settlers found – and almost immediately began filling – are still there. We can’t see them until heavy rains come. Then the ground quickly saturates and the floodwaters rise.

Wagley said the practice of trying to bury wetlands and creeks isn’t unique to Pensacola; it has been done almost everywhere. In Pensacola the Spanish, who established a permanent settlement in Pensacola in 1698, began the filling; the British continued it in creating the garden plots that became Garden Street, and in the 1880s and ‘90s the city finished off the remaining downtown wetlands by dumping municipal garbage as well as debris from a big downtown fire.

Another buried creek, which might be a future tour, flows underground to the east, past St. Michael’s Cemetery to an ancient wetland we now call Aragon.

Mead argues that “daylighting” San Gabriel creek — removing the asphalt, dirt and debris covering it — to restore the old creek basin would help control flooding, reduce flood insurance premiums, improve water quality and create an attractive green corridor that could be lined with walking paths.

And, counter-intuitively, it should also facilitate development on the west side of downtown.

There is a surprising amount of undeveloped, and underdeveloped, land along the creek basin, which is still discernible despite the apparent flatness of downtown. Mead said the high water table and saturated, mucky soil make it expensive to build stable foundations. One moderate-sized building required digging out and replacing 15 feet of muck with red clay. I later talked to a builder who confirmed the difficulty of working in that part of town.

Daylighting has been done successfully elsewhere, sometimes paid for with bonds repaid out of new tax revenue produced by property tax growth from new development.

It would likely cost millions of dollars to uncover the estimated 3,000 linear feet of San Gabriel Creek that could feasibly be daylighted. Mead holds out hope that it could be part of a comprehensive downtown drainage solution, and suggests it could even be cost-competitive with trying to replace old drainage pipes with bigger ones.

Which is ironic when you consider that had we simply lived with the creek as nature designed it, we would have had all these benefits for free.

The outfall of what was Washerwoman's Creek near the sign for Nick's Boathouse in downtown Pensacola.[/caption]

In downtown Pensacola, we were told, the wetlands and creeks the Spanish settlers found – and almost immediately began filling – are still there. We can’t see them until heavy rains come. Then the ground quickly saturates and the floodwaters rise.

Wagley said the practice of trying to bury wetlands and creeks isn’t unique to Pensacola; it has been done almost everywhere. In Pensacola the Spanish, who established a permanent settlement in Pensacola in 1698, began the filling; the British continued it in creating the garden plots that became Garden Street, and in the 1880s and ‘90s the city finished off the remaining downtown wetlands by dumping municipal garbage as well as debris from a big downtown fire.

Another buried creek, which might be a future tour, flows underground to the east, past St. Michael’s Cemetery to an ancient wetland we now call Aragon.

Mead argues that “daylighting” San Gabriel creek — removing the asphalt, dirt and debris covering it — to restore the old creek basin would help control flooding, reduce flood insurance premiums, improve water quality and create an attractive green corridor that could be lined with walking paths.

And, counter-intuitively, it should also facilitate development on the west side of downtown.

There is a surprising amount of undeveloped, and underdeveloped, land along the creek basin, which is still discernible despite the apparent flatness of downtown. Mead said the high water table and saturated, mucky soil make it expensive to build stable foundations. One moderate-sized building required digging out and replacing 15 feet of muck with red clay. I later talked to a builder who confirmed the difficulty of working in that part of town.

Daylighting has been done successfully elsewhere, sometimes paid for with bonds repaid out of new tax revenue produced by property tax growth from new development.

It would likely cost millions of dollars to uncover the estimated 3,000 linear feet of San Gabriel Creek that could feasibly be daylighted. Mead holds out hope that it could be part of a comprehensive downtown drainage solution, and suggests it could even be cost-competitive with trying to replace old drainage pipes with bigger ones.

Which is ironic when you consider that had we simply lived with the creek as nature designed it, we would have had all these benefits for free.

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs