Pre-K lessons from the Mountain State worth looking at

- August 12, 2016

- / Shannon Nickinson

- / education

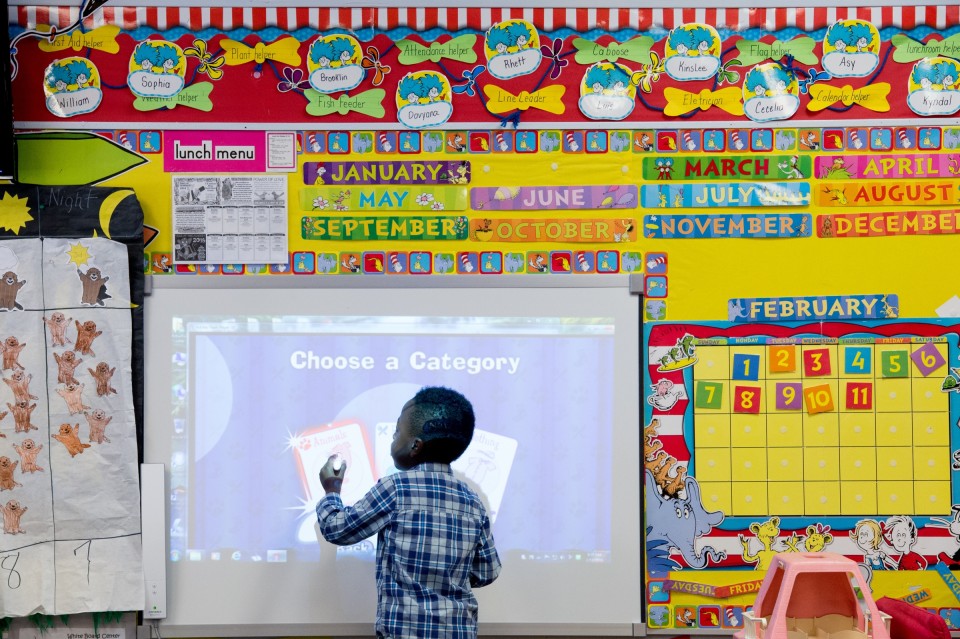

Asy McCray uses a Mimio Board at T.R. Jackson Pre-K center Thursday February 11, 2016 in Milton, Florida. (Michael Spooneybarger/ CREO)

NPR featured a story highlighting preschool programs that are getting good results. The story focused on a report by The Learning Policy Institute, which offers snapshots of four state programs.

Some of the high points:

Michigan: Targets families who make up to 250 percent federal poverty level; 80 percent of children attend a full-day program. Overall funding is increasing, but per-slot funding is decreasing as enrollment rises. State dollars per child: $6,447.

Washington: Modeled on Head Start and provides extensive wraparound services for families. Targets 3- and 4-year-olds whose families earn no more than 110 percent federal poverty level. Funding is $7,000 per child for part-day; $9,960 per child for full day. Funding from Gates Foundation helped set up quality metrics for all providers to be rated on.

North Carolina: Targets child ages birth to 3 in families who earn 75 percent or less of state’s $51,000 median income. All-day program. State requires all early childhood programs to get a quality rating. Providers must get 3 out of 5 stars to continue receiving state subsidies. The state gives higher reimbursement to better rated facilities. Two programs offer scholarships and wage subsidies to early childhood professionals. Teachers get three years of coaching before they get a full credential of their own. Per slot funding: $5,200 a year.

West Virginia: Open to all 4-year-olds and 3-year-olds with special needs. Funding is built into the K12 funding formula. The statewide participation rate is 75 percent, just a point or two off of Florida’s statewide participation rate. It will move to five-day a week, full-day programming this school year. Funding per pupil: About $6,200.

West Virginia is the state where I began my journalism career, covering education, in the mid-1990s. The legislation for the universal Pre-K system in West Virginia came after my time in there, originating in 2002, according to Monica DellaMea, executive director of the West Virginia Office of Early Learning.

“We look, generally speaking, we look at readiness in terms of are the families ready, is the school ready to support the family as they enter first grade?” DellaMea says. “We view school readiness as looking at first-grade entry. Kindergarten and Pre-K are grouped together as early learning readiness grades. We know that kindergarten and Pre-K are alike programmatically. They build from one to the other.”

The system began with basic framework and guidelines in 2004 and in 2008, the state Board of Education set equal state-aid funding for all Universal Pre-K students, regardless of setting. In 2013, kindergarten was deemed by state law as an “early learning grade” alongside Pre-K.

DellaMea says that Gov. Earl Ray Tomblin built into the policy that set up the Pre-K system the linkage between the Pre-K and kindergarten years.

“We have our Pre-K kids built into state funding formula,” DellaMea says. “When our lawmakers speak about the education system, they are speaking a language of a P-12 system. We know that’s not the case everywhere. We try not to take that for granted.”

That’s an important point.

IMPACT ON SALARIES

Considering preschoolers part of the full public education system may help influence another set of numbers — preschool teacher salaries.

In the Pensacola metro area, the average preschool teacher earns about $20,570 a year — with a median hourly wage of $9.89.

In Charleston, W.Va., the state’s capital city, the average preschool teacher earns $34,530 a year — with a median hourly wage of $16.

Because Pre-K students are considered part of the full public school system, the West Virginia Early Learning Reporting System (ELRS) creates a report that kindergarten teachers can see on their incoming students.

It summarizes each child’s performance in social and emotional development, language and literacy development, mathematics, science, arts, and health and physical development. Teachers also may add information about each child.

Five years ago, DellaMea says, the state began to work on building a uniform data collection process that included training for preschool teachers in how to collect the data. The system is built around standards from the National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER) at Rutgers University.

“Expansion of public Pre-K is only a worthwhile public investment if children receive a high-quality education,” the NIEER authors wrote in the 2015 report. “Unfortunately, even many of the states that have chosen to fund pre-K have not committed sufficient resources to fund a high-quality program.”

NIEER issues a report card on the state of the nation’s preschool systems. Florida meets 3 out of 10 benchmarks on that report card for 2015.

West Virginia is one of seven states in the nation that meet all 10 benchmarks. Florida early learning officials note that NIEER’s quality measures are “inputs” — teacher training, student-staff ratio, health and service screenings offered. It doesn’t measure the quality of interaction between the adult in the classroom and the 4-year-olds in her care.

But Florida has failed in recent years to maintain a reliable measurement of readiness because of changes to the Florida Kindergarten Readiness Screener that made comparing the results across time impractical. For the last two years, no new kindergarten readiness rates have been released by the state because of problems with the test and testing procedure.

Read more about that here and what it can mean for VPK providers here.

DellaMea says the 2015-2016 school year was the first “non-field trial” year for data collection.

“We wanted to make sure teachers were trained to collect the data,” she says.

Data is collected on children three times a year in the Pre-K year and twice a year in kindergarten, DellaMea says. (That’s similar to the VPK assessment done two-three times in the VPK year in Florida and the Discovery Education assessment used by Escambia County schools on kindergartners.)

“Young children are very unreliable,” DellaMea says. “So we don’t put children in front of a computer and ask them to perform. We work on helping teachers collect good evidence.”

She says the assessment they do is very similar to Work Sampling Survey, which was one half of the Florida Kindergarten Readiness Screening.

When the universal VPK program began, 50 percent of the programs had to be collaborative with a community partner — a childcare center or Head Start. By 2015-2016, 81 percent collaborative.

“If a county engages with a private center, they still have to uphold our state policy. That’s helped us in NIEER quality benchmarks,” DellaMea says. “We have made this commitment to young children, knowing the return on investment is much greater than the cost.”

Among the highlights of the 2016 report to West Virginia lawmakers on the program:

— Nine percent of West Virginia’s kindergartners were significantly below their grade-level expectations in language arts by the end of kindergarten.

About 15 percent of Escambia kindergartners are significantly below expectations in reading at the end of the kindergarten year.

— In Kanawha County, home of the state capitol, Charleston, state funding covers an average of 6.4 instructional hours a day for prekindergarten. The state average is 6.7 hours.

Florida’s VPK “day” is funded for three hours of instructional time per day.

Beginning this past school year, NIEER and Marshall University in Huntington, W.Va., began to collect data on children in the Mountain State’s universal Pre-K program for a long-term study on the benefits of universal Pre-K. Seven counties are part of that study.

— Preliminary data show that children in the state’s Pre-K program performed better than children who didn’t attend Pre-K in all four assessment areas — vocabulary, print knowledge, math and executive function.

— Third graders who attended a WV Universal Pre-K Program as a 4-year-old scored 4.1 percentage points higher on average in language arts than their peers who did not attend a WV Universal Pre-K Program.

One other number of note.

Florida spends about $2,400 per child on its VPK program. That’s less funding now than when statewide VPK program began in 2005.

And it’s about one-third of what the states highlighted in the Learning Policy Institute’s report spend.

Is money everything? No, but it is a pretty important thing.

For the coming school year, Florida will spend $7,178.49 per pupil in the K-12 system.

Imagine if our 4-year-olds were considered “full citizens” of the public education system. What benefits might they — and by extension our public schools and communities — be able to reap?

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs