Weis working to change community from the roots

- September 19, 2016

- / Shannon Nickinson

- / early-learning,education,report-meeting-the-challenge

Teacher Perry Merritt in her Pre-K class for 3-year-olds at C.A. Weis Elementary School.

This is the first in a series of installments on the improvement plans principals are implementing at the 11 Escambia County elementary schools that received a D or F on the Florida Standards Assessment.

The staff at Weis Elementary School want to change their community from roots.

ABOUT THIS SERIES

Learn how Holm Elementary is working to improvement achievement among its students.

Learn how Warrington Elementary plans to boost student achievement.

Learn how Sherwood Elementary focuses on parent outreach and teacher training for school improvement.

Learn how Global Learning Academy is striving to overcome the challenges of poverty to increase proficiency.

Learn how Lincoln Park Elementary is working to strengthen relationships among staff, parents and community.

Learn how Ensley Elementary is planning to boost math and reading skills as part of the school’s improvement plan.

Learn how Oakcrest Elementary is building stronger relationships to increase student learning.

Learn how West Pensacola Elementary is helping students and teachers get resources to improve academic achievement.

Learn how Montclair Elementary is reaching out to the community and increasing parental engagement to improve student achievement.

This year, they’re starting with 3-year-olds, in Perry Merritt’s preschool classroom at the school on Q Street. There are 15 students in the classroom, where learning basic school socialization rules is built into the day, along with centers to learn sorting, colors, counting, shapes, and more.

There’s time for art, for pretend play, for storytime and for building skills on the computer. There is also a waiting list that could support a second classroom, says Principal Holly Magee.

“The need is there. We were shocked at the waiting list,” Magee says. “Our goal is to keep growing, and to keep going younger. We want to be doing more in the 0 to 3 space.”

Merritt, who started her teaching career 26 years ago at Navy Point Elementary School, is in her fourth year at Weis. She volunteered for the K3 class because she thought that some of her students would benefit from getting into a school setting sooner.

Weis is home to a Community School, a project that includes Children’s Home Society, the University of West Florida, Sacred Heart Hospital, Escambia Community Clinics and the Escambia School District.

The aim is to make the school a true hub of the community and offer the kind of wrap-around services that parents in the west Pensacola neighborhood and their children need most to help counter the effects of poverty. It is modeled on Geoffrey Canada’s Harlem Children’s Zone, and represents a significant community investment in the nearly 500 children at Weis and their families.

Advocates believe that investment will pay off for students now at the school and will help break the cycle of generational poverty that challenges those children physically, academically and socially.

Weis is one of 11 elementary schools in Escambia County that received a D or F on the 2016 Florida Standards Assessment test. Magee, in her third year as principal, and her staff of 42 teachers have a focused plan to help their students improve.

They also don’t want to be paralyzed by a standardized test.

“I’ve been proud to see that three of my teachers put their own children here. That’s really saying something,” she says. “We have great teachers here.”

Among the pieces of Weis’ strategy for the coming year:

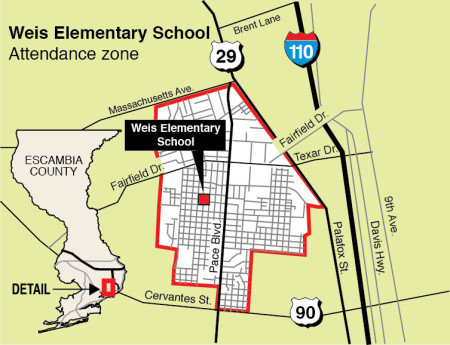

C.A. Weis Elementary, North Q Street.

Enrollment: 477.

Teachers: 42.

Demographics: 72.5 percent African-American; 8.1 percent white; 4.4 percent Hispanic.

Special education students: 82.

Free- or reduced-price lunch rate: 77.5 percent.

— After-school enrichment. On Aug. 15 Weis launched an after-school program, funded partly with a 21st Century Grant submitted by Children’s Home Society for the school. The grant totals $1.5 million dollars split among the next five years — about $350,000 a year.

Magee says the program has a capacity for 120 kids, but the staff was strategic in the students they chose for the program. First, they use FSA data and targeted students in third, fourth and fifth grades who needed reading help.

The curriculum for the after-school program matches what the school-day curriculum does.

But because many of the older students at Weis babysit younger siblings after school, Magee said if a student was picked for the program, all of their siblings were eligible for it, too. They also took applications at orientation: “We have more applications than we do slots right now,” she says.

The program includes a snack, a community meeting, an hour of reading, enrichment activities (including a dance class, Spanish classes, running clubs for boys and girls) and a hot dinner. It wraps up at 5:30 p.m. It will continue into the summer, but what format that will take is yet to be determined.

How can Magee tell progress is being made?

Meal service from the district for those dinners was not ready for the first week. Within a couple of hours, partners from the community and the Community School had stepped up to make sure that dinner was covered for the first week until district meal service could be put in place.

That kind of community response wouldn’t have happened five years ago, Magee says.

As part of the 21st Century Grant, six parenting classes must be included. Magee says they surveyed parents to find out what they wanted to see in those classes. Financial management, how to shop on a budget, how to pay your bills and budget your money.

— Clinic is growing. The Weis Wellness Cottage is a pediatric clinic so it offers all health care needs including wellness appointments, sick visits, and immunizations. It is fully staffed with 2 examining rooms. Magee says it’s been eye-opening to find out, for example, that some Weis parents who never have gone to a well-baby appointment before go to the clinic where they learn the developmental milestones a 1, 2, or 3-year-old should meet. “They didn’t know that,” she says. “It’s been a great thing for our parents.”

Through the clinic, parents get referred to resources to help with access to food, for example, or whatever they need.

— Parent engagement. Weis now has a parent resource room, open for whatever parents need. One mom recently used it to fill out an online-only job application. That mom, for example, stayed at the school to help volunteer in the front office for a couple of hours.

Weis has about six family nights a year, (which include dinner), but Magee wants parent involvement to be more than coming to watch the class musical performance or art show.

“We want them to be integrated into the school, and they are,” she says. “We have parents now who say, when we see your car up here, we’re watching out for you. And it’s not that I think I need anybody, but now that’s such a change from two years ago.”

“It’s really changing the school. Our school grade doesn’t show it and I know that. I think it will soon.”

“When we started here we had four windows shot out, three with BB guns. My first day (two years ago) was July 4 up here because people were setting off the alarms trying to break in. And then last year, we had nothing, because people are really starting to see the school as part of the community. I really believe that. Our parents watch out for the school now because the school watches out for them.”

The University of West Florida, one of the key partners in the Community School project, has given the school a doctoral candidate to build the parental engagement side more.

— Targeted reading intervention — for low- and high-scoring students. We have almost half of our students tested already so we have made progress with that, so they are getting targeted instruction they need. Walk and read, where students might not stay with the same teacher during that time because that teacher might not be working at that moment on the thing they need more reinforcement on. They will travel to another teacher’s room for their specialized intervention. That includes targeted instruction for students who are on higher reading levels so that.

— Vertical team planning. As a pilot, Magee has a first-, second- and third-grade teacher working together to take the global view of grade level planning to make sure that what’s happening in first grade is supporting what needs to happen in second grade and so on.

"Our data shows our lower quartile scores aren’t bad; 44 percent of our lowest quartile are moving but we’re missing out on our higher kids. We’re not moving them. With the vertical team, they could step over to a third-grade teacher to get more challenge.

“In a school like ours when our kids come to us so far behind, it’s natural to want to focus on the largest group,” Magee says. “You’d do that wherever you were.”

— Training for teaching in high-poverty schools. Weis has 14 new teachers this year, some of whom have never been in a high-poverty school. Weis teachers come in for a week in the summer for “Weis Academy”, a time for them to get familiar with the community and some of the challenges of teaching in a high-poverty school.

All Weis teachers are trained in a model of “trauma informed care” so that they can recognize when behavior in school has a root-cause in something else.

That’s part of what the classroom community meeting that starts every day in every classroom at Weis is about.

It’s a way for students and teachers to take the pulse of the room to help head off issues before they come up. Kids have to answer: how are you feeling today; what is your goal for today; and who can help you meet that goal.

It helps build the network of support that is at the root of trauma-informed care — and that is critical for children from backgrounds where stress, anxiety and poverty often form a toxic cocktail that hurts their development.

— Tools to teach social skills. Weis teachers also are trained in a curriculum that gives K-5 teachers strategies to teach social skills — something usually done before a child enters kindergarten.

“Teachers knew their students didn’t have the social skills needed, but they’d never been taught how to teach those skills,” Magee says. “By giving them something to use, they just took off with it.”

Just four or five kids in a classroom who were still struggling with the basics of following rules does two things: It draws more of the teacher’s time to those students, time she couldn’t spend on lessons; and it encourages other kids to copy those who weren’t following the rules.

This year, one of the Weis teachers will have a classroom space for students who are lagging in those social skills. It’s not a special education class, but a class for student who need a little more focus on how we act at school. It’s not a punishment space, it’s a therapeutic setting. Once a child’s behavior improves, he or she can go back to their regular classroom full-time.

— Support for teachers. Weiss added a second behavior coach and a curriculum coordinator at the school for this year.

— Filling the food gap. Weis is in a food desert — Magee says it is on average 10 miles to the nearest grocery store offering fresh produce. The school is continuing the weekend backpack program, an outreach effort of First Baptist Church, to help families who need food to get through the weekend. Weis sends home about 360 backpacks a weekend.

— Tracking data. There are extensive data sheets in shared drive where teachers can see and track the progress of each child, so that teachers can realize students are making growth.

The drive lists, for example, every reading standard. In each reading test, a student’s performance in noted in each standard. It’s time-intensive, but Magee says it is a way to see where specifically children are struggling and growing.

Teachers then will enter into that database how they will remediate students who need help, and followed-up with to see how that strategy worked.

While the Florida Standards Assessment is a reality of life, Magee says she works hard to send the message to her staff that it is not the only thing that matters about their school — and their students.

Last year, watching Magee’s own son started kindergarten. Comparing how he progressed to how Weis’ kindergartners progressed was “eye-opening.”

Magee’s son went to daycare. While many Weis students come from childcare centers, not all of them are “academic based” centers, Magee says. “They are not prepared to come into a social situation where they will have to sit and be quiet and take turns, eat with utensils.”

Some are staying with grandma “and grandma has five others she’s watching and she’s doing what she did when she was a mom raising kids.”

Given the changes in what is asked of 5-year-olds now in school, the learning strategies of a generation ago are not enough to get those little ones where they need to be.

At the end of October, when Magee’s son’s kindergarten teacher told her that almost all of his class was reading, and “my kids were still learning to sit down in the cafeteria and eat appropriately, it was huge for me.”

“It’s not that our kids can’t get there, they can,” she says. “The road has to look different (to get them there).”

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs