Shannon's Window: On the street where you live

- October 12, 2016

- / Shannon Nickinson

- / education

Crews work on a new home being constructed in the East Hill neighborhood in Pensacola, Fla., Thursday, December 5, 2014. (Michael Spooneybarger/ Pensacola Today)

Neighborhoods matter.

As more research and literature emerges about early learning and the impacts on brain development of language and early education, something else emerges, too.

The more we sort ourselves in neighborhoods by economic standing, the more children we risk leaving behind.

In May 2015, a study by Raj Chitty of social mobility used IRS data to look at tax returns filed by people from the 1980s until 2014. It shows how far behind Escambia County other communities.

It showed that a child born in Escambia County had a poor chance of rising above their economic circumstances if the neighborhood they were born in was a poor one.

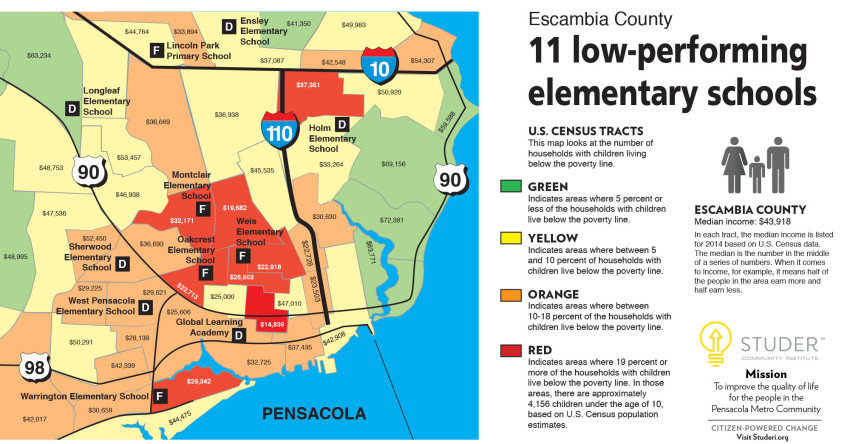

When you look at this map that marks where the 11 lowest graded elementary schools in Escambia County are, that idea becomes more than a statistical abstract.

It is our cold, hard reality.

A map of the elementary schools graded D or F according to the Florida Standards Assessment.

Credit: Ron Stallcup.A paper published by Dr. James Heckman, a Nobel Laureate in economics from the University of Chicago, adds a layer to this conversation.

“The Scandinavian Fantasy”, deals with Denmark’s much-lauded investment in making sure that high quality preschool education is available to every child — regardless of family economic status.

Such an investment is good at closing the cognitive gaps between rich and poor children in Denmark.

But it doesn’t produce any greater economic social mobility than is seen in the U.S.

“Our findings point to wage compression and the higher levels of welfare benefits as being counterproductive in providing incentives to pursue education,” they write. “The sorting of families into neighborhoods and schools by levels of parental advantage is likely another contributing factor. While the Danish welfare state may mitigate some childhood inequalities, substantial skill gaps still remain.”

Because even in Denmark, neighborhoods still matter.

“The generosity of the Danish welfare state does not prevent sorting of children into neighborhoods and schools on the basis of family background, which appears to benefit the more advantaged,” the authors write.

That sorting of neighborhoods by housing patterns — which are tied to education and income levels — is something the Pensacola area has struggled with.

While work progresses on the apartments being built downtown by Quint and Rishy Studer where the Pensacola News Journal used to sit, other large pieces of developable land remain fallow.

Hawkshaw — once again up for marketing as local media outlets note — has failed to materialize into anything more than a grassy knoll. At least three attempts to sell it — and get it off the public dime and onto the property tax rolls by the way — have failed as the city’s Community Redevelopment Agency (which is City Council), opted to wait for a better offer.

Last year, it was noted that the Pensacola area was 3,000 housing units short of filling the need for affordably priced housing. Half of Escambia’s households are rent-burdened — paying more than 30 percent of their monthly income for housing.

The cost of renting has risen in the region and shows no sign of easing.

On Oct. 11, Mayor Ashton Hayward issued a viewpoint saying he would have city staff build a list of city-owned properties, sell them and put the proceeds “to provide funds for new or existing housing programs. Some of these lots will be bundled with homebuyer assistance programs to help qualified families finance homes in mixed-income neighborhoods.

“By utilizing for-profit and nonprofit developers, federal and state incentive programs, and local private investors, we intend to manage our city-owned infill properties in a manner that can serve as a model for the growth of mixed-income neighborhoods and lead to the elimination of “pockets of poverty,” the statement reads.

“The intended result: a transformative mix of new affordable and market rate housing that will improve neighborhoods and provide more people with a place to call home in the City.”

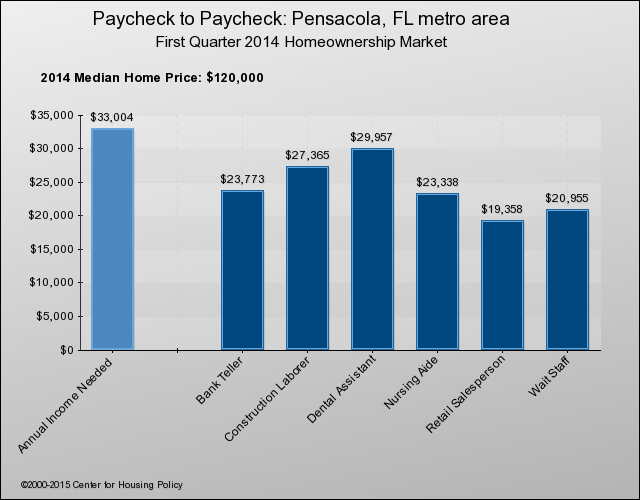

Hayward references the Florida Housing Commission’s 2016 report that finds the wages we pay many workers don’t add up to enough to afford a home.

Median wages by industry for men and women in the Pensacola metro area. Source: American Community Survey

Some 8,000 children under the age of 5 live in the poorest Census tracts in this county. How far behind are we willing to let them and their families be?

The answer will determine more than the educational and economic prospects of those children.

It will influence the tax base, which pay for schools, cops, roads and drainage systems.

It will influence the education system that will have to remediate ever more students, robbing other students of the attention and inspiration teachers can offer them, too.

It will influence the crime rate, the value of property, and the kinds of wages we command.

It will speak volumes about the kind of community we want to be.

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs