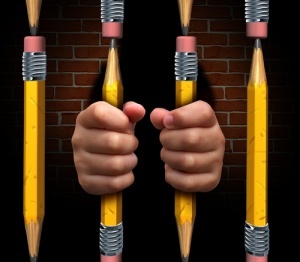

Breaking school-to-prison pipeline

- May 19, 2014

- / Reggie Dogan

- / community-dashboard

A student is more likely to be arrested and possibly face felony charges for fighting in Florida than any other state in the nation.

The Sunshine State leads the nation in school-based arrests, and the school-to-prison pipeline is funneling students out of the classroom into the criminal justice system at alarming rates, says the American Civil Liberties Union.

Keyontay Humphries, regional organizer for the ACLU in Pensacola, says Escambia County incarcerates more children per capita than any other county in the state.

“Schools have a role to play to fix this growing problem,” Humphries says. “In the schools, there is a failure to provide intervention, remediation and support for these children.”

Humphries is working to raise awareness of the issue. She recently spoke at Bethel AME Church in an event sponsored by Pensacola Community Partners (Rebuilding the Village).

In 2011-12, Escambia County sent 865 children to detention centers and 219 young people to juvenile prisons, Humphries says.

During that same time, Florida recorded the highest number of school-based arrests in the country. About 12,000 students were arrested 13,870 times in Florida public schools, according to a report in the Orlando Sentinel.

Most of the arrests, 67 percent, were for infractions like fist fights, dress-code violations and talking back – misbehavior that, in Florida and other places, increasingly results in misdemeanor criminal charges.

Humphries says she’s currently working on a case that involves a second-grader in Escambia County who was arrested for excessive crying. Even though the Sheriff’s Office dropped charges, the child’s family is pursuing civil charges, Humphries says.

“Through bias and negative perceptions, they now have put in place policies and laws that set children up to fail,” she says. “These laws are strong on punishment that pushes children out of the classroom into the prison system.”

Too many of these children, according to data, are black or Hispanic.

Statistics show that students of color are more likely than their counterparts to get caught in this destructive pipeline of punishment.

Across the U.S., the race gap in student punishments is wide, according to the Department of Education civil rights data from 2011 to 2012. Black students without disabilities are suspended or expelled three times as often as white students without disabilities. Students with disabilities, often emotional or behavioral disorders, are also overrepresented in suspensions, the data show.

As a result, they drift from graduation by harsh punishment – suspensions, expulsions and even arrests – that leave them disenfranchised and more likely to quit school and become trapped in the criminal justice system.

Donna Curry, a retired human resource manager for Exxon Mobile attended the event.

Curry says she said is concerned about statistics that put Escambia County high on the list for arresting children.

Schools, she says, used to be a safe haven for children, but not any more.

“If schools are not a safe place, and kids can’t get an education, they end up in prison, can’t get a job or take care of their families,” she says. “We have to do a better job than just kicking them out.”

Curry says while the problems are many, the “blame game” is not the answer.

“Each of us must come together to do our part,” Curry says. “We have a lot of work to do with the school system, the Sheriff’s Office and the parents.”

Humphries says community leaders too often point to poverty as the root cause of the problems in schools and the community.

“To blame poverty alone is not justification for the problems,” Humphries says. “It is disgraceful for the stakeholders to say it’s everybody’s fault but their own.”

Steps to fix the growing problem of children getting entangled in the criminal justice system, Humphries says. Include community involvement, parental engagement and teachers and principals taking an active interest in a child’s social development, not just his or her academic achievements.

Other ways to help, Humphries believes, include more accountability, voter participation, sensitivity training on gender and race for teachers and using data to highlight patterns and behaviors.

It will take some policy changes and public education to cut the flow of the pipeline, Humphries says.

“Criminal justice is for punishment,” she says. “Juvenile justice is about rehabilitation.”

[progresspromise]

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs