Pensacola or Baltimore?

- May 15, 2015

- / Randy Hammer

- / economy

Let’s say you are a parent and you’re poor and you have a young daughter.

Would she have better economic opportunities in life if she lived in Escambia County or Baltimore?

Think about it. You’ve seen the pictures, the TV reports, the riots.

Escambia or Baltimore?

A new study says Baltimore.

The Impacts of Neighborhoods on Intergenerational Mobility by two Harvard professors asks the question: To what extent are children’s opportunities for upward economic mobility shaped by the neighborhoods in which they grow up?

The answer: A lot.

And while boys who grow up poor in Escambia fare better than boys who grow up poor in Baltimore, both counties are among the worst in the nation for children who grow up in low-income families and neighborhoods.

I ran across a story about the study in The New York Times last week. Here’s the quote that caught my attention:

“Escambia County is extremely bad for income mobility for children in poor families. It is among the worst counties in the U.S.”

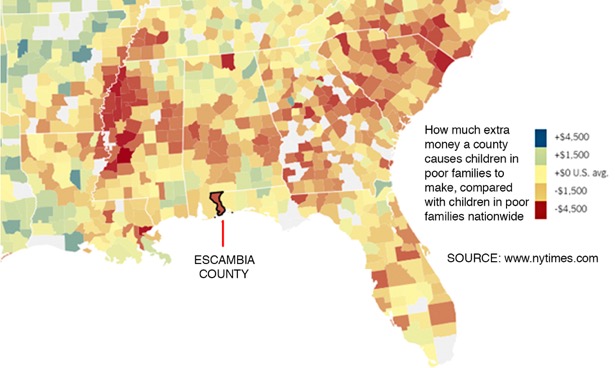

The New York Times story includes an interactive map that’s labeled, “The Best and Worst Places to Grow Up: How Your Area Compares.” The study and the map reveal that “children growing up in some places go on to earn more than they would if they had grown up elsewhere.

I’ve spent most of my life here. I raised my children here. And I absolutely love this place. For me, the area has been great. But this study and the map are depressing because it’s clear Escambia County is not such a great place for a lot of people, especially poor people.

The story doesn’t mince words about Escambia:

“It’s among the worst counties in the U.S. in helping poor children up the income ladder. It ranks 47th out of 2,478 counties, better than only about 2 percent of counties. It is relatively worse for poor boys than it is for poor girls. Although bad for poor children, it is somewhat better for higher-income children.”

Rick Harper, the Studer Community Institute’s senior research fellow and a University of West Florida department head, also found the report depressing.

The study shows that “you can take the kid out of the community, but you can’t take the community out of the kid,” Harper said.

What stood out to him:

— Kids who grow up in and around the Pensacola MSA earn about 8.4 percent less than the same kid would if he/she were to grow up in an average place in the U.S.

— For Escambia County, the results are even worse. Kids who spend 20 years of their childhood in Escambia earn about 15 percent less at age 26 than the same kid would if they grew up in an average place in the U.S. That’s $3,870 a year less than in the "nationally average" place.

— Escambia is second worst among the 67 counties in Florida, with only Gadsden County registering lower, at -$3,910.

— Nassau County, north of Jacksonville, is the best performer in Florida, with a child who spent 20 years there earning $2,240 more than the national average.

Harper’s key takeaway: “Pick your friends wisely, because your hometown matters, and it matters with whom you grow up.”

Earlier this week, Quint Studer addressed more than 150 people at the Institute’s Hiring Talent workshop at Hillcrest Baptist Church. During his opening remarks, he talked about the Institute’s focus on improving the area’s quality of life.

“The issue here is truly the wage index,” he said.

The Harvard study is a dramatic testament to that.

I hope you’ll take time to read The New York Times story and study the interactive map that appears with it. Escambia clearly stands out on the map and not for the reasons we would like.

We cannot fix this problem overnight.

Our only hope is if our schools, businesses, churches, synagogues, not-for-profits and political leaders decide to truly make the less fortunate among us a community priority.

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs