Eglin's plans for the Blackwater

- June 27, 2014

- / William Rabb

- / government

Opponents of an Air Force plan to conduct special operations training in two state forests are breathing a small sigh of relief after a state oversight council put off a decision until early next year.

But the friends of the forest say their fight is far from over, and documents show the military is looking at other state, federal and private lands all across Northwest Florida.

“We stopped the fast train, but it is still parked on the siding,” said Barbara Albrecht, who works with the Bream Fishermen Association and is a watershed specialist with the University of West Florida.

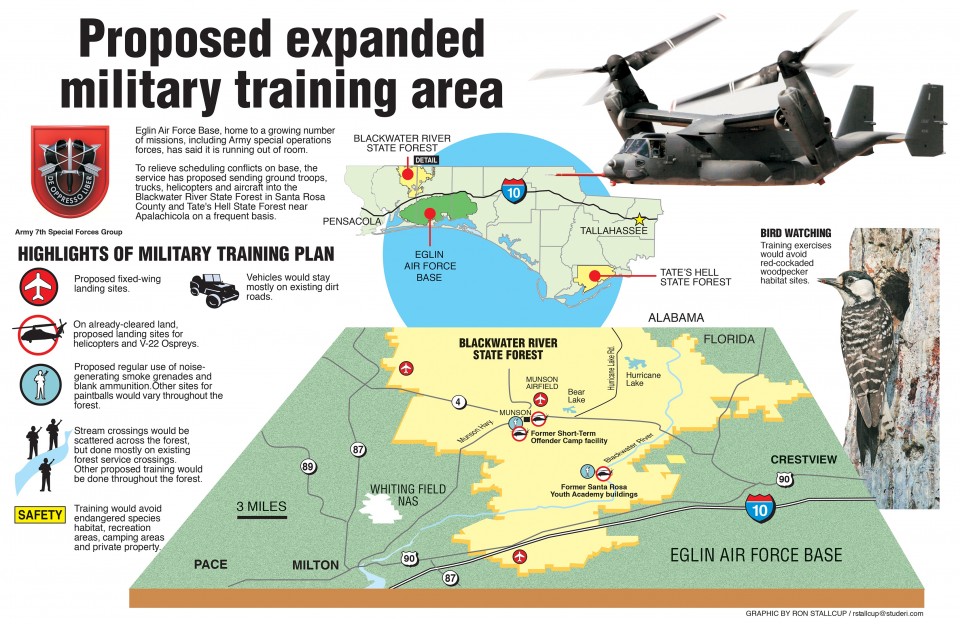

Eglin Air Force Base, home to a growing number of missions, including Army special operations forces as well as the military's most expensive weapon, the F-35 fighter jet, has said it is running out of room.

To relieve scheduling conflicts on base, the service has proposed sending ground troops, trucks, helicopters and aircraft into the Blackwater River State Forest in Santa Rosa County and Tate's Hell State Forest near Apalachicola on a frequent basis. The public comment period on the plan closed this week, and the Air Force is expected to make a decision on the plan by late July.

The Air Force, if it decides to proceed, would then apply formally to the Florida Forest Service. And while state Agriculture Commissioner Adam Putnam, who oversees the Forest Service, has expressed strong support for the military maneuvers, the final say may rest with the state Acquisitions and Restoration Council.

The 10-member council, appointed by the governor, the agriculture commissioner and the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commissioner, reviews management plans for all state-owned lands. Staff Director Hank Vinson emailed concerned citizens this week that the council would wait until after the Air Force presents a finalized environmental impact study of the proposed training, and probably won't meet on the issue until February 2015.

The council must review “any military training activities on state-owned conservation lands before the FFS (Florida Forest Service) or other agencies allow them,” Vinson said in the email.

Other state lands are certainly in the military's sights. Even if special forces training utilized the two state forests to the maximum extent outlined in the plans – as much as 232 days a year – it wouldn't be enough, said Mike Spaits, public affairs officer for Eglin.

“That would only reduce our requirements by about 10 percent,” he said.

The Air Force also has signed memoranda of agreement with the Northwest Florida Water Management District, the state Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and the state Department of Environmental Protection. Those agreements have received little attention in the debate over Eglin's expansion proposal, but some of those lands also are environmentally sensitive, activists said.

It's not certain which of those agencies' lands would be considered. Although the agreement called for a draft operations plan to be done by summer 2013, a water district official said the district is still waiting on that from the Air Force.

The district owns almost 225,000 acres, mostly along waterways. Protecting these riparian zones from vehicle traffic and other disturbance is important for keeping rivers clear of silt and maintaining the health of bays and estuaries, Albrecht said. (The Environmental Protection department lands would only be used for siting equipment that emit radar signals to aircraft, according to the memorandum of agreement.)

But that's not all. The Air Force also is eyeing national forests and some of the miles and miles of private timberland that stretch across the Panhandle, Spaits said. Blackwater joins the Conecuh National Forest in southern Alabama. To the east, Tate's Hell forest abuts Apalachicola National Forest. Both are within two hours' drive of Eglin, a key concern for the Air Force.

While the Army and National Guard for years have staged war games in a few national forests around the country, and have held minor maneuvers in the state forests, the push for additional space is something new.

At a 2012 meeting with Florida's governor, an Air Force official explained Eglin's new way of thinking: “That's where opportunities lie...on the parks and state forest land, conservation lands, and some private lands with willing partners that we think are out there as well.”

To many Floridians, it seems unimaginable that Eglin, the world's largest Air Force installation, with 460,000 acres, would be running out of space.

“Why can't they re-evaluate some of their missions and get better use out of the space they have?” asked Santa Rosa County Commissioner Bob Cole, who has two sons in the military and typically considers himself supportive of the armed forces training requirements. His district includes part of the Blackwater Forest, and he has raised concerns about the damage that helicopters and heavy trucks might do to forest habitat.

When the crowding began

The apparent crowding at Eglin appears to be largely the result of good intentions set in motion almost a decade ago.

The Base Realignment and Closure Commission in 2005 recommended that bases across the country be closed to trim defense spending, and Congress agreed. The commission sent the Army's 7th Special Forces Group, with 2,500 personnel, from Fort Bragg, N.C., to Eglin, in part because the Air Force Special Operations Command was already at Hurlburt Field, on the southern edge of Eglin. And the military is increasingly stressing joint operations between branches.

Another joint operation is the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, which has been called the most advanced fighter plane ever built. Air Force, Navy and Marines will use it and all three branches now train at Eglin, which is home to 100 F-35 pilots, with more on the way.

Air operations at Eglin, including takeoffs and landings, are expected to top 427,000 annually by 2018, when the full complement of 59 strike fighters arrives. That's more than double the number of flights a decade ago, according to Eglin data.

Eglin's primary missions are to train pilots and test and evaluate airborne weapons systems. That means much of the base's scrub and forestlands are reserved for bombing ranges and missile targets. By law, those missions take priority over what are known as “non-hazardous” special forces ground training, Spaits said. That's why the base began exploring other options, particularly state lands, he said.

The state forests were considered first, “because the Forest Service was so supportive of our plan,” said Mike “Pappy” Penland, the Air Force senior policy analyst who spearheaded the expansion plan for eight years.

The state forestlands also come at a good price.

A tentative lease fee, shown in the draft operations plan, asks for $382,000 annually for the use of Blackwater and Tate's Hell, plus a one-time fee of $123,000, although that is subject to change, Forest Service officials said. Purchasing additional property for military training would be too expensive for the Air Force, according to the impact statement.

And leasing private land would undoubtedly cost more than what the Forest Service is charging, said Bruce McCormack, a Florida defense contractor who has tried to broker a deal to lease to the military some 90,000 acres of privately-owned forest land near Blountstown.

Some of the 1,500 public comments about the forest training have suggested the military also consider other private timberlands, including about 380,000 acres stretching from Bay to Leon counties now owned by an affiliate of the Mormon Church. Spaits said those and other areas would be considered at some point.

Conservationists concerns

Some of those who want to keep state lands reserved for wildlife, hunters, kayakers, horseback riders and hikers don't have much faith that Florida will ultimately refuse any of the military's requests, in the state forests or other lands.

After all, the military is the Panhandle's largest employer, and Gov. Rick Scott has said he hopes to make Florida the “most military-friendly state.”

“If they let it happen in Blackwater and Tate's Hell, I'm sure they'll be moving into other state forests and state parks and state lands,” said Peggy Baker, a member of the Northwest Florida Audubon Society, one of the few environmental groups to flat-out oppose the training maneuvers.

A limited number of troops already have been quietly training in the state forests. Records obtained by Progress+Promise show that in the last year, the Army's 7th Special Forces Group requested and was granted permission on four occasions to conduct exercises, mostly at night and mostly in and around an unused youth camp facility in Blackwater.

The permits, like the proposed operations plan, stipulate a number of actions the soldiers must avoid, including taking vehicles off designated roads, cutting trees, digging holes, and camping near the endangered red-cockaded woodpecker nesting trees.

On those occasions, “they came in, they left; I never knew they were there,” said forester Thomas Ledew, who was manager of the Blackwater River State Forest for seven years until he retired late last year.

Ledew has some concerns about the impact on the forest, and would like to make sure that the Forest Service can pull the plug if it's shown the troops are causing too much damage. But for the most part, Ledew, who was involved in the Air Force discussions for three years, believes the training will have little impact on habitat.

“A lot of environmentalists may hate me for saying this, but I say we ought to give it a try,” he said. “Let's see if we can work together.”

A “multiuse forest”

The Blackwater forest, long considered a “multiuse forest,” already has a number of areas that are kept cleared by the Forest Service to attract game species for hunters, Ledew said. Those spots are ideal for helicopter landings, as suggested by the Air Force's operations plan, he said.

The Air Force has said the training would have minimal impact on the ecosystems, and soldiers would go to great lengths to mitigate damage and avoid endangered species. No live ammunition would be used (although some soldiers would live off the land by trapping wildlife to eat). Eglin's operations, in fact, have won a number of awards in recent years for their stewardship of the environment, and ground forces would bring that same philosophy to training on state lands, officials said.

Not all environmental groups are hostile to the martial maneuvers.

The Nature Conservancy has said conservation and military go “hand in hand.” Some conservation groups contend that military interest helps ensure that state forestland will never be sold for commercial development.

That may actually be a possibility for some state lands: Gov. Scott's administration is avowedly pro-business, and in 2011 offered to close 53 state parks as part of environmental-protection budget cuts.

But the Blackwater is somewhat protected from commercial development, Ledew said. The federal government once owned much of Blackwater. The land deed contains a “reverter clause” that stipulates that if the land is ever sold, ownership must revert to the federal government. The draft operations plan, while calling for a 10-year lease agreement, also stipulates that the Air Force or the Forest Service can cancel the agreement with only a 90-day notice.

Threatening the Blackwater’s comeback?

In the first half of the 20th Century, loggers practically scraped parts of Blackwater and Tate's Hell clean of old-growth timber, crisscrossed the land with logging roads, and replanted it with fast-growing pine suitable mostly for commercial purposes. But thanks to a program of controlled burning in recent years, Blackwater is now part of the largest continuous longleaf pine ecosystem in the world, which also makes it one of most ecologically diverse systems, Florida Forest Service documents show.

Today, the 210,000-acre forest is in the midst of a comeback, with more than 181 species of birds, including bald eagles and a growing population of red-cockaded woodpecker. Tate's Hell forest is home to black bear populations and other threatened species.

Blackwater's champions are particularly proud of an effort to close 434 miles of unneeded dirt roads and limit erosion that can silt up estuary habitat. The Yellow River is now the swiftest-flowing in Florida and one of the most pristine in the state.

Military vehicles, amphibious landings and foot traffic would threaten all of those gains, Albrecht said.

“Millions have been spent bringing these forests back,” she said. “Why would they jeopardize all that?”

The Forest Service, Albrecht, Baker and others say, has been too supportive of the military's expansion, and has been less than forthcoming about the training plans. Although the Forest Service signed a memorandum of understanding with the Air Force in late 2012, the agreement was not well publicized in local media.

Members of an advisory group, charged with writing a 10-year management plan for the Blackwater, say they were never told about the military initiative until after the management plan was nearly finished in 2013.

Agriculture Commissioner Adam Putnam said through a spokesperson this week that the management plan was already in the works when the Air Force approached the state. Ledew pointed out that the Air Force plans, until this spring, weren't specific enough to know the extent and location of the operations, so they weren't detailed in the forest management plan.

The environmental impact statement on the proposed training, commissioned by the Air Force, also has not played by the rules, critics charge: It doesn't offer alternative plans that may leave a smaller footprint on the forest, a violation of the National Environmental Policy Act that all federal agencies must follow.

The Air Force project manager, Mike Ackerman, said the draft impact statement is “just a starting point,” but declined to comment further.

To others in the Panhandle, anything to do with defense spending can't hurt the area.

“I don't see how it (the forest training) would be good or bad for the economy here,” said Larry Sassano, president of Florida's Great Northwest economic development agency, based in Niceville. “We have always been supportive of the military and they have been supportive of the community and the environment, too.”

The maneuvers could impact the economy of the Blackwater forest itself, some have said.

If the helicopters and troops move into the western edge of the forest, near the popular horse trails, “then horseback riding in the forest will decline,” said Medora Mullins, who lives on private land inside the forest and is an avid rider. “Camping at the Coldwater Recreation Area would decline, and forestry revenues would be adversely affected.”

Training required a change in federal law

The proposed leasing of state lands for extensive, regular military training is such a new concept that it required a recent change in federal law.

In February, Congress added one paragraph to the Farm Bill, which makes state forestry services and other state agencies eligible for federal funds if they work with the military. The Air Force cites that law as one authority for the proposal.

The Farm Bill was sponsored by an Oklahoma congressman, and U.S. Rep. Jeff Miller, R-Pensacola, whose district includes much of the Panhandle, voted for it. Miller's office said it was unclear who added the language about the military cooperation, but that it wasn't Miller.

U.S. Sen. Bill Nelson, D-Melbourne, has not been outspoken about the forest plans.

“The Air Force is now reviewing the public comments they’ve received on the environmental impact,” he said this week. “And I’ve made it clear they need to consider all sides on this issue.

[progresspromise]

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

CivicCon launches with a look at good growth in cities

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

Building stronger brains one baby, one parent at a time

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

SCI debuts commercial on Early Learning City

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

Entrecon: World class speakers and an opportunity to sharpen skills

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

PYP Quality of Life survey 2017

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

EntreCon Pensacola 2016: A look back

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: getting better employee takeaways

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: be interested instead of interesting

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Leadership tip: delivering difficult messages

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs

Brain Bags boost Arc, Early Childhood Court programs